That's a piece of bone from said foot protruding above the surface.

We had tendered in to Charlestown, Nevis

>

>

a small island whose larger sister, St. Kitts, we had previously visited.

Its modern history begins with confusion. In 1493 Christopher Columbus on his second voyage was the first European to view the island and named it San Martin. Evidently the navigation aids weren't very good in those days, because the name was accidentally applied to another island, some 50 miles away. So it was up to someone else – one not as illustrious as Columbus, because the author is unknown – to come up with another name.

It turned out to be much more expressive than the original: based on a 4th century Catholic miracle, a snowfall on the Esquiline Hill in Rome, it was "Nuestra Seņora de las Nieves," or "Our Lady of the Snows." It is hypothesized that the white clouds that usually cover the top of Nevis Peak reminded someone of a miraculous snowfall in a hot climate. Of course, such a long name was often abbreviated, and over time it became simply Nevis.

This was not to be the last time Columbus' wishes were ignored – his completely reasonable designation a few weeks later of a Rich Port on the island of Saint John was somehow reversed to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

But I digress.

Charlestown, the capital, is a small town (population 1,500), on a small island (eleven by six miles), but historical in several respects, and we toured the highlights.

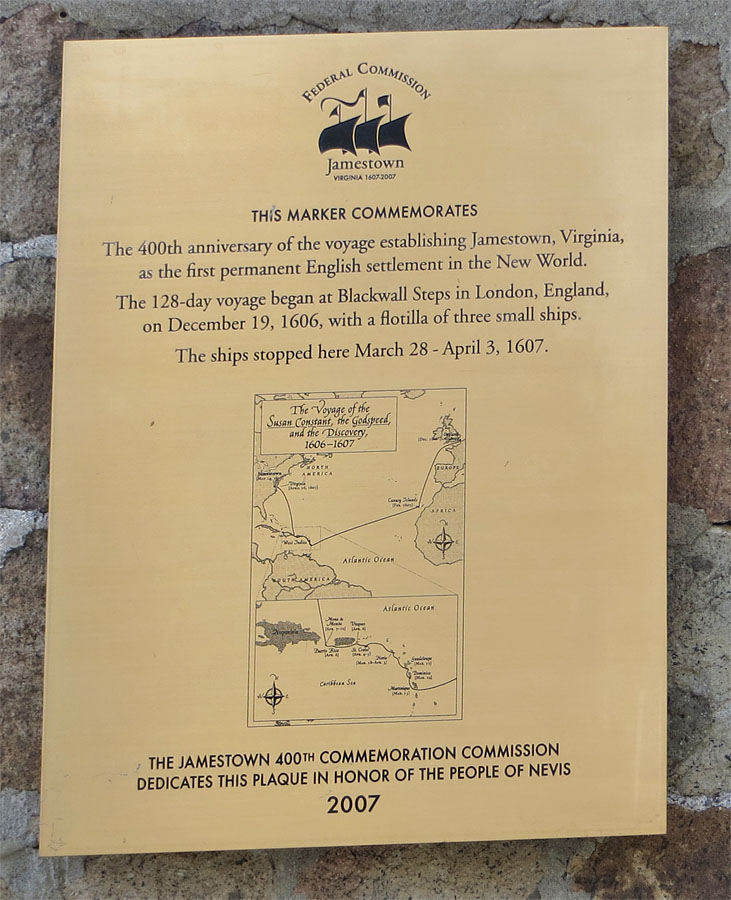

For one, who knew that this was a stepping stone for the settlers of Jamestown settlement?

Actually, that's a rhetorical question – I'm sure there are those among my extensive list of erudite correspondents to which that's no surprise.

The harbor, featuring an engine that perhaps once powered a cotton gin,

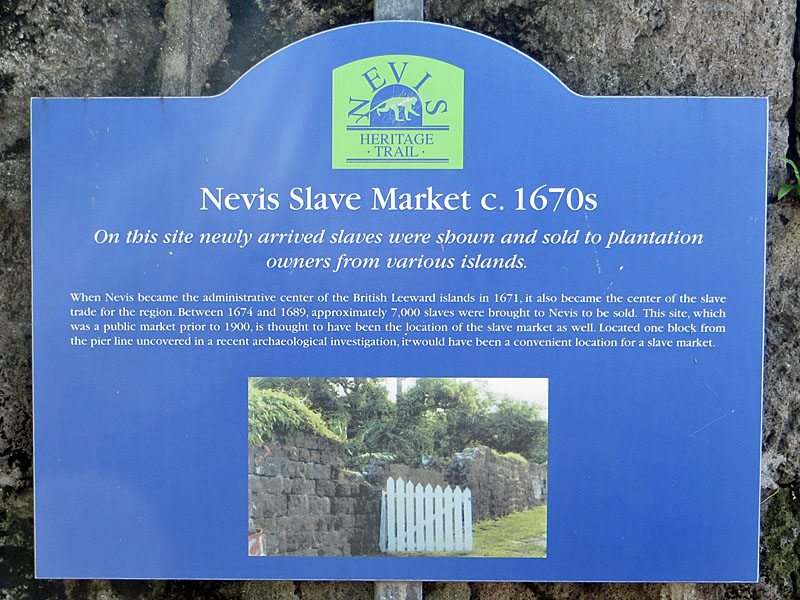

alludes to Nevis' history as the center for the distribution of slaves throughout the British Leeward Islands. Unlike St. Kitts, for example, where references were made to "sugar estates" rather than plantations, they are not afraid to address the sins of the past.

Even before slaves were freed in 1834 the Oxford-educated rector of St. Paul's Anglican church, who believed slavery was wrong, began classes for slaves and their children in the church school to the right.

On our way out of town, our patronage was solicited along the way.

The Catholic church was still decorated for the holidays.

Scuttling crabs dotted the stony shore. Although the sea was clear, the sandy beaches were a few miles farther out of town.

The recent hit play, Hamilton, only mentions that he was born "in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean."

This is that spot.

Built in 1680 and destroyed by an earthquake in 1840, it has been reconstructed to its original form and now, in addition to displaying Hamilton artifacts, also incorporates a historical museum. We've read that these days the Hamilton cast recording plays on a continuous loop.

Other broad-brush references from the play describe his father's desertion, and his mother dying of an unknown fever, after they had moved to St. Croix.

He had already become a clerk for an import-export firm, where he was flung headlong into, as biographer Ron Chernow puts it, "a fast-paced modern world of trading ships and fluctuating markets.... He had to mind money, chart courses for ships, keep track of freight, and compute prices in an exotic blend of currencies, including Portuguese coins, Spanish pieces of eight, British pounds, Danish ducats, and Dutch silvers." He thrived and later said it was "the most useful part of his education."

However, further adversity followed him: after his mother's death, he and his older brother lived with a cousin for a year and a half – until he committed suicide. His fortunes now turned: while his brother was apprenticed to a carpenter, he was adopted by a wealthy merchant. A voracious reader, he had assembled a modest collection of books at an early age, and now took advantage of his benefactor's more extensive library to hone his reasoning and writing skills.

Ironically, another tragedy, this time a natural one – the 1772 hurricane Maria that devastated St. Croix and many other Caribbean islands

became his passage to America.

The eloquence of his first-hand account of the violent experience was printed in St. Croix's "The Royal Danish American Gazette," which gained so much renown that

A closing line of his departure

actually relates to the reason there are few remembrances of his time here – he was seen to have turned his back on his humble heritage. He never returned nor provided any aid to the West Indies islands of his youth. Of course, he had ample reason to close the door on that part of his life, which he never revealed to anyone.

Further into town, we discovered a small art gallery featuring works of expatriates from colder climes, then stopped into a liquor store, which was also a local gathering place. Several people sat around, enjoying a cold beer from the refrigerated case and conversing with each other. The proprietor invited us to join them, and we would have if they'd had WiFi, but we needed to check-in to our too-soon-upcoming return flight.

As we strolled towards the pier, Betty Lou asked a young woman heading in the same direction if there was a nearby location with WiFi, and she recommended the Cotton Ginnery Mall, to which she led us. As the name implies, it's a repurposed cotton ginnery, with the ground floor now including a variety of shops, and the second the customs office and the Blessings Restaurant – which was owned by our guide's family.

However, she didn't steer us wrong – in addition to having WiFi, the second-floor open-air location was pleasant on a typically warm and humid day and whose vantage point provided enough advance notice of incoming tenders to leisurely proceed to the pier. When we ordered beers, Bobby stepped out, no doubt to the liquor store to replenish his stock – we could see there was only one behind the glass refrigerator door. The soup listed on the blackboard menu had caught my attention, and when Bobby returned, I had to try it.

He said it was like a stew, with the meat on the bullfoot adding a beefy flavor. It had a taste of cloves, and there were tasty gelatinous morsels and several dense, but delicious, dumplings. It was hearty enough that I'm glad we resisted also ordering the "Steam Callallo."

The chalkboard menu didn't include prices so when we were ready to leave I was surprised to learn that the total was 42 dollars! That did include, by then, three beers – total, that is – we didn't want to have Bobby make another trek to the liquor store. However, I was relieved to learn that was in East Caribbean dollars, which translated to 16 US dollars.

We had spent a good part of a day exploring Nevis, but we didn't spot any of the green vervet monkeys that have overrun the island. They're not just in the interior – on our previous stop at St. Kitts, we'd read of a Charlestown resident who had complained, "They don't run. They don't hide. They come in open daylight to your property and eat the hell out of your food. They're a bloody nuisance, and their economic value here is negative. The only good they do is, some tourists who come here like to look at them. But I think we should have dancing girls instead. They're nice to look at, and they don't eat as much fruit!"

Unfortunately, we also didn't see any dancing girls.

While researching Hamilton's life I found an unsung hero: his mother, Rachel. Born to a well-to-do St. Croix family, John and Mary Faucette, a pleasant life seemed to lie before her. However, that was before John Michael Lavien, a dapper Danish rogue trailing a history of failed businesses and an eye for someone with money appeared on the scene. That Rachel was also a beauty was an added incentive.

Lavien's fine clothes and tales of successful investments persuaded her mother to force Rachel into marriage, at age 15. He proved to be an abusive husband and after she had a son, Peter, the next year, no more followed – she was also a strong-willed woman. His unfortunate investments continued, financed by her dwindling inheritance, until she left him at age 21.

Outraged, he had her clapped into the infamous Fort Christiansvaern. He assumed that after several months of imprisonment in a small dank cell with fare of salted herring, codfish, and boiled cornmeal mush, she would come crawling back to him.

Au contraire – she had spunk!

Upon release, she fled to St. Kitts, where she met and fell in love with a Scotsman, James Hamilton. Hamilton himself was an inept businessman, but he was well-meaning and had been continually bailed out by wealthy older brother John in Scotland.

They moved into the property she had inherited on Nevis. Since women were unable to secure a divorce, James Junior, born two years later and Alexander after two more years were labeled in St. Croix as obscene children, a powerful stigma in those days. However, in Nevis she could be known as Mrs. Hamilton. (Lavien later had no impediment when he decided he wished to divorce, and with another nasty twist – Rachel was forbidden to remarry! If you wonder how that could be enforced, any cleric who performed the ceremony would be fined or dismissed.)

For 15 years it seemed like the family was well on the way to a brighter future, when James was asked to go to St. Croix to collect a debt for his employer. It was to be a prolonged process. Since Lavien had moved to the opposite side of the island, and Peter was now in South Carolina, Rachel felt safe in returning with the boys. The proceedings dragged on for a year, but after their successful conclusion James left, for reasons still unknown.

Not to be defeated, with some financial assistance from relatives she started a small business. She sold plantation supplies she purchased from the import-export firm down the street (where Alexander later clerked) from the first floor of the home where they lived upstairs. She proved to be an astute businesswoman – a total anomaly among the male-dominated hierarchy. She kept good books, paid her bills on time, and was able to purchase on credit.

Once again it appeared a secure future lie ahead of them, until a fever struck her and Alexander. Although he recovered, she did not, succumbing at age 38. Now the vengeful husband swooped in, convincing a magistrate that any of her estate belonged to the legitimate son, leaving Richard and Alexander homeless and penniless.

It is clear that Alexander's intelligence and strong sense of purpose came from his mother. A resilient role model, she rebounded time after time from adversity, only to be eventually felled by disease.