• In the fall of 2021 a CT scan revealed several lesions (tumors): one in the tail of my pancreas, one in the nearby stomach wall, and two in the spleen! They couldn't all be biopsied non-invasively, so a surgical oncologist recommended the removal of sections of the pancreas and stomach wall, and all of the spleen. (I was assured that one doesn't absolutely need a spleen; that vaccinations can replace its disease-fighting capability.)

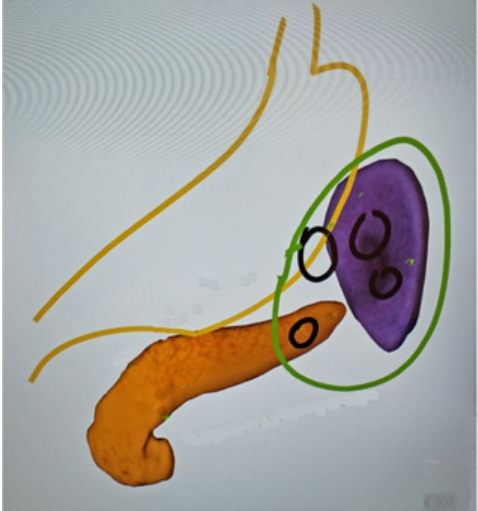

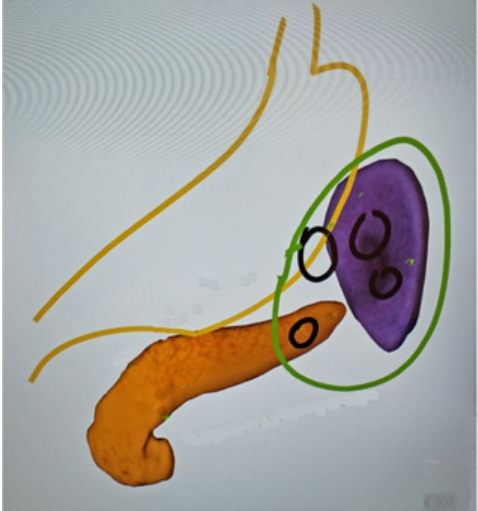

This is his diagram of what would be involved.

He called up the display of the pancreas and spleen on the lightbox that was normally cycling through tips on how to stay healthy or when to buy a new toothbrush; he drew in the stomach. The black circles indicate the locations, but not the sizes, of the various lesions.

He said it was about as easy as such an operation could be, although it seems that it would have been easier without the incursion into the stomach. It was laparoscopic, although removing the spleen required its own incision above my navel, which is not noticeable today. (Unfortunately, someone later mistook the relatively uncomplicated distal pancreatectomy for the more complex Whipple procedure, and I haven't been able to get the record corrected.)

He didn't quite agree that he could do it in his sleep, although November 29th he did do it in my sleep.

However, when Medicare statements arrived, I realized that perhaps it wasn't as simple a procedure as I thought. One hospital item showed 68 total units of sterile supplies, totaling $79,539! The surgical record did note that "Sponge, needle and instrument counts reported as correct at the end of the case."

• In any case, things went well, and after five days in the hospital, I returned home. There was the additional inconvenience of a Jackson-Pratt drain tube from the abdomen. A suction bulb at the end of the tube had to be emptied four times a day and the total recorded. Between emptyings, the tube was taped to my chest, the main inconvenience. It was finally removed December 28th, a belated Christmas present.

Meanwhile, the pathology results had come back. Fortunately, the lesions in the stomach and spleen and two they discovered in the liver were all benign. Unfortunately, the one he removed in the tail of the pancreas was cancerous.

However, it was still completely within the pancreas, and the eight neighboring lymph nodes tested negative, so I thought all was well. But it was so close to the edge of the incision and pancreatic cancer is so deadly that the possibility that even microscopic particles could have escaped that two oncologists recommended chemotherapy. 1

Almost everyone I've told of my experience knows of someone who had it, but it wasn't caught in time, and they died. I've personally known three, I've since learned of many more famous people, and now I'm noticing how often others appear in the newspaper.

The chemotherapy choices were like Goldilocks:

• By February, I had completely recovered from the operation and was ready to begin chemotherapy. However, even this course – a weekly gemcitabine infusion and three capecitabine tablets soon after breakfast and dinner for three weeks, followed by a week off before beginning the next series, over a scheduled six-month period turned out to be disastrous.

At first, all went well. Eventually, some known side effects occurred, including mouth sores and a rash on my neck and back. Then, at my third Tuesday infusion, a test showed I was dehydrated. On Wednesday they gave me an IV of 500 mL, 1,000 on Thursday, and on Friday they took me to the emergency room!

I had initially arrived for an IV at 11 AM, but the emergency room was busy, and we waited quite a while for a cubicle to become available where they could make further tests. It was a Friday, the waiting room became increasingly crowded and police began to arrive; initially with what might have been a drug overdose, then with a combative man.

Eventually, around 7 PM, a cubicle became available, and as far as I was concerned, apart from my initial complaints I felt fine, joking with the staff and drinking ginger ale. However, my condition gradually deteriorated, and eventually I couldn't walk or swallow or, Betty Lou says, speak intelligibly, so she had to translate! By the time they found a room for me on a specific floor it was 2 AM.

In fact, without Betty Lou I would been lost. She stayed overnight with me in the rooms – there were several over the course of my stay – taking notes and correcting staff as necessary. She learned which were the best items in the cafeteria, and with all the miles of walking the halls lost 30 pounds herself. She would return home some time during the day to keep things going and eventually to clear out enough space in the living room for a hospital bed. Even after I returned home, I was not much help for another month.

• The hospital stay itself added its own drama, much of which was preventable. A few days after the Gastro tube was implanted in my stomach to provide nourishment since I wasn't able to swallow – it proved defective and exploded. It took two more trips to Interventional Radiology to replace it.

An angioplasty with three stents in my left leg became necessary ;2 and the insertion of a tube in my right arm 3 resulted in a blood clot in my shoulder 4 and serious edema in my arm, requiring a snug wrapping and glove to cause it to subside. Fortunately, a May 26th ultrasound revealed the blood clot had dissolved; an earlier one before my release showed it was still present.

After seven weeks, including several weeks of daily occupational, physical, and speech therapy 5, on April 12th I was finally able to return home 6. Fortunately, just before I left, a third test showed I was able to swallow liquids, although only a teaspoon at a time.

It had been nearly two months when the only liquid allowed was from melting ice chips. Although I was well aware of the restriction, a notice by the door and all references to my treatment warned others "NPO," nil per os: nothing by mouth. I'd been longing for a taste of ginger ale for all that time!

• With regular visits from occupational and physical therapists, I was able to walk unaided by the end of May a much appreciated milestone! Assisted by visits from a speech therapist, I'd also been able to eat and drink normally 7. Gradually I'd progressed from puréed to soft pieces to regular food, initially between sips of water. I had lost 60 pounds from the beginning (the tumors) in fact, I weighed less than the nurses! I don't intend to gain it all back, but I'm now back to my high school weight!

• As for how the chemotherapy led to my disastrous situation, my recent research indicates it was probably related to the capecitabine. A medication called 5-FU has been used for chemotherapy; capecitabine generates 5-FU and has been found to be more effective in treatment. An enzyme called DPD removes 5-FU from the body, however 2% of the population have a DPD deficiency and risk severe toxicity. In fact, 10% leads to death, of which it's estimated 700 to 1,400 occur annually in the U.S.

Europe requires testing for this deficiency, but not in the U.S. – instead, the FDA "suggests physicians discuss the possibility of testing with patients." Even that did happen with me, and a test was not ordered until I was entering the hospital.

The results showed that I lacked the DYPD 2* mutation; however, it has been found to be associated with only about half the cases of extreme enzyme retention. Tests for three other mutations, c.2846A>T, c.1679T>G and c.1236G>A/HapB3 have been found clinically-relevant predictors of toxicity, but I received none of them. During my hospital stay, I exhibited some of the serious symptoms warned about, so maybe I was a fortunate survivor of an undiagnosed deficiency.

• Another anomaly is that my hearing had decreased 20 dB in the speech range e.g., Betty Lou's since my last test. And there was a problem involving my left shoulder I couldn't raise my arm more than about 90°. I could move it to full extension with my right arm that is, it wasn't a blocked joint. It may have been related to some overzealous manipulation of my shoulder by the home occupational therapist.

Consultations with an orthopedic surgeon, an osteopath, and a neurologist who ordered an MRI weren't able to determine a reason. Fortunately, several months of treatment by an expert physical therapist gradually restored normal movement, which was a huge relief. The "expert" is because a previous round of treatment by another had had no effect, and I was becoming concerned that the condition could be permanent. Fortunately, it appears the cause was a pinched nerve that the physical therapist's manipulation eventually relieved.

• Also, because of the sudden weight loss, my veins had collapsed so much that it became difficult to find one from which to take a blood sample. Even today there have been occasional difficulties placing an IV, e.g., for insertion of contrast fluid during CT scans.

• As for the usual chemo effects, my hair had thinned substantially, although not my beard, but the growth has returned to normal. And fortunately, to date, three CT scans 8 show "no evidence of new metastatic disease or pathologic lymphadenopathy," and all remaining organs are normal or at least for "patient's chronological age!" I'll be getting such scans regularly in the future as a precaution. 9

While in the hospital, I said this was the first time I'd felt my age, but now I'm back to my youthful self again! 😉

1 I've often thought that if the incision was a little farther away, my story might have happily ended at that point. 🙁

2 A CT scan revealed that some time in the past I had developed obstructions in veins in both legs, but collateral circulation had built up around them, similar to what had happened previous to my heart attack. Evidently, even when back problems curtailed my running after forty years, normal activities were sufficient to maintain the collateral blood vessels' flow around the blockages.

However, my prolonged inactivity in the hospital resulted in their closure, which may have been prevented by the use of sequential compression devices on my legs. They had been provided during the pancreas operation and afterwards in the Reston hospital, but only for the first few days, of seven weeks, in the Arlington hospital. Ironically, their equipment's operation had been much less intrusive than the earlier ones.

As for the angioplasty itself, the morning it was scheduled, they realized a medication that needed to be stopped 24 hours in advance had not been. The next day the original cardiologist was not available, so they brought in another from their practice in Manassas. He said he would not use stents, which I appreciated. However, the procedure was more complex than he anticipated and in the end, three were necessary.

Also, perhaps because the procedure took longer than expected, the anesthesia wore off! Not that I totally woke up, but I was able to tell them that I was in agony and to please do something! "Calm down, take it easy," was their response! They did eventually accede to my pleas – perhaps they had to send out for more fentanyl!

Afterwards I complained about it to several doctors, each of whom seemed totally unconcerned about the situation! Perhaps it happens all the time!

Although blood flow resumed, the left foot and toes no longer have normal flexibility, initially leading to the erroneous conclusion that I had drop foot, a more serious condition. Unfortunately, PT and six months of a twice-daily one-hour application of a DynaSplint, which applies a calibrated pressure on the foot to increase the range of motion – the pressure being gradually increased over time – did not increase flexibility.

3 The PICC (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter) line was used to draw blood and provide medication. I later realized that it was an unnecessary addition; the mediport connected to my jugular vein that had already been inserted under the skin of my chest for chemotherapy infusions could have been used to provide the same access.

However, that would have required the services of an oncology nurse, which they were reluctant to request. Although the oncology facility, Virginia Cancer Specialists, was located nearby in the hospital, it is not a part of the hospital organization!

Even the installation of the mediport had been mishandled. The date of my first infusion was known over a month in advance, but for some reason the insertion of the mediport wasn't scheduled until after the first infusion. An arm vein had to be used instead, which turned out to be quite painful.

4 The blood clot, in turn, required a daily injection of Lovenox under a fold of the skin of my stomach – including for another two months at home, which Betty Lou administered.

5 These daily hour-long sessions were only begun as I was on my road to recovery. Of course, they were intended to gradually improve my capabilities over time, but in my weakened condition they could become quite exhausting.

6 There was an earlier ill-fated two-day stay in the Cherrydale Health and Rehabilitation Center. It had not been our first choice, but more desirable facilities were fully booked, including one which we were told was known as the "Three Yachts" one!

I was taken there on a Friday evening after the doctor had left for the weekend, and the pharmacy required for several medications was not, as might be expected, the one at the Safeway a block away, but 40 miles away in Columbia, Maryland also not available on the weekend.

After a female nurse had several times successfully performed the rather tricky procedure of adding Creon delayed-release pancreas enzyme granules to the feed tube, a male nurse, from the same sexist culture from which she came, refused to accept her advice, and it became clogged. (After the operation, I had been able to take them in capsule form, but now that I could not swallow, and because of the delayed-release property they could not be crushed, they had to be carefully portioned out into the feed tube.)

So an ambulance returned me to the hospital, and by the time they were able to unclog the feed tube, a vacancy had become available in their rehabilitation unit. At least, in this case, a pleasing outcome resulted from a disappointing beginning.

7 Swallowing involves a complex series of actions, many of which are involuntary, the most important being the closure of the "windpipe" by the epiglottis, a thin flap of cartilage, and the temporary inhibition of breathing while food passes by to the esophagus on its way to the stomach. Without these actions, food and other particles could enter the lung and lead to severe infection and even death.

The swallowing tests began with saliva, progressing to different textures and sizes of liquid and food in my case, not very far. Initially, a fiber optic endoscope through the nostril was used, which could view the action of the epiglottis; the next two were by fluoroscope, which could monitor the entire swallowing process, from mouth to stomach.

8 The results of one CT scan included that the appendix, in medical-speak, "is visualized and is unremarkable." Actually it would have been quite remarkable, since my appendix had been removed when I was twelve. Evidently that area was not very clearly defined because others had hedged their bets with "Appendix is not definitively visualized."

I remember that time well because after the operation, I was placed in the children's ward and the rascals delighted in trying to get me to, painfully, laugh.

9 Update: Unfortunately, eventually a CT scan revealed a new concern..