Two o'clock on Wednesday morning, April 3, I suddenly awoke with some strange sensations: a headache, which I never have – occasional slight feelings of nausea and shortness of breath – and an ache in my right shoulder blade.

The shoulder blade ache was the most concerning, since it was one of the unusual symptoms eventually leading to the discovery of a heart attack in 1992! That time, despite assurances from first the company nurse, then a rescue squad, I requested to be taken to the hospital, where the cause of the unusual sensations was finally determined.

This time, I skipped intermediate steps and called 911. A fire truck soon arrived out front, fortunately without siren to disturb the neighbors, although the bright flashing lights might have attracted some notice. I told them that we didn't have a fire, but they said they always do this, and that an ambulance would soon arrive. I also noticed that they were from Fairfax, not Arlington. They said it's because they were the nearest responder.

But I digress. The truck's equipment included a portable EKG, which this time did show some anomaly. The ambulance arrived, I climbed in, and after some time to strap me down and hook me up, we leisurely headed to what I still think of as Arlington Hospital, but after several name changes is currently VHC Health.

The EKG administered by the Emergency Room doctor determined I had a STEMI (ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction). The ST refers to a segment of the EKG pattern that is normally flat at the baseline and relates to the ventricles, the lower chambers of the heart.

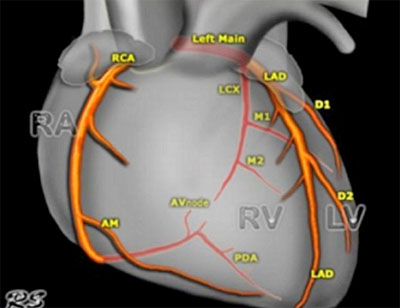

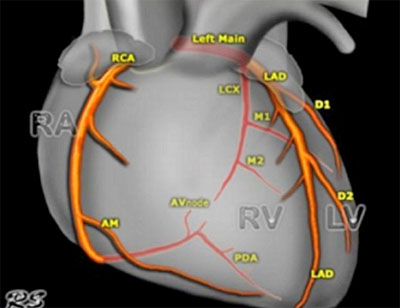

The right ventricle pumps blood returning from the body to the nearby lungs. The left ventricle pumps oxygenated blood returning from the lungs to the farthest reaches of the body. Infarction is a blockage of blood flow to the heart muscle, the myocardium. In other words, particularly if it involved the left ventricle, it was a serious event, and I was wheeled into the Catheterization Lab.

I was fortunate that the Interventional Cardiologist on duty, who was towards the end of her shift, was a renowned specialist, because the procedure encountered complications.

My right wrist was strapped down to avoid inadvertent movement, and a catheter was inserted. I remained conscious during the procedure. An overhead robotic arm moved the X-ray source from position to position as the doctor guided the catheter to my heart, through the aortic valve into the left anterior descending artery. This time the clot was in one of its diagonal branches, the D2.

Initially, the doctor said that it appeared that the wire in the catheter was not going to be able to penetrate the clot, so she may have to withdraw it and depend on medication. I didn't ask, but it's possible it was similar to the clot dissolver that was used the previous time.

However, she persevered – the robotic arm occasionally whirred from one spot to another – and eventually the regular beep, beep, beep of the heart monitor changed to a rapid and erratic beeping, which soon returned to normal – the clot had been cleared and fresh blood was rushing into the artery.

Similar to the previous time, a balloon was inflated to expand the narrowed artery1. The artery was too small for a stent to be inserted, if one may have been indicated. In any case, none was installed after my earlier AMI, which was in the early days of stents, and the affected artery has remained open for over 30 years.

Or at least if 21 treadmill stress tests and 10 echocardiograms since then can be believed.

I had been relatively comfortable during the procedure, except where an IV needle in the back of my hand was strapped down against the table. However, I was reminded of the potential seriousness of the situation when they peeled two pads off my back – pre-positioned in case a defibrillation was necessary!

The catheterization notes did not include begin and end times, so I'm not sure how long the whole procedure took, although the doctor signed the report at 5:57 AM. She came by at the end of her shift to see me in the ICU and diagramed on a whiteboard the location of the blockage.

Another cardiologist arrived soon after and announced that since everything had gone so well, I could leave that afternoon if I wished! Compare that to my previous experience, when the sequence of events took a week.

I decided to stay overnight just to be sure, was moved from the ICU to another floor and left the next afternoon.

1 The report said that the procedure performed was "Plain Old Balloon Angioplasty (POBA) to D2." I guess cardiologists have a sense of humor. However, it's likely they got the idea from the POTS (Plain Old Telephone Service) previously provided by copper land lines.

A later echocardiogram revealed the disconcerting fact that the Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) was now 45. The LVEF is the percentage of the blood in the left ventricle that is pumped out with each contraction. Normal is considered to be 50 to 70. After the previous heart attack it was 65, and it had been recently measured at 67.

Although the D2 artery is only a narrow branch off the much larger left anterior descending artery, its effect was greater in this case. The reason is that in the previous situation collateral circulation had built up around the narrowing artery as it eventually approached a 90% blockage, so the difference when a clot created a 100% blockage was not that great. This time, the clot suddenly appeared, and the lack of blood flow in the part of the D2 artery beyond it resulted in loss of heart muscle.

Over the last several months I had been regularly visiting the gym, including time on the treadmill. I've already noticed some breathlessness after climbing stairs, but doctors have assured me that medications and cardio rehab will improve the situation in time.

Update: A July echocardiogram indicated that the ejection fraction had improved to 50. After completing a three-month, three-times-a-week course of cardio rehab in August, I've returned to the gym.